Every Festival (The Festival)

“I wanna be a part of it”

(New York, New York – Fred Ebb & John Kander)

The first edition of the Jeonju Film Festival took place in 2000, a good time for film festivals. Its opening film was Virgin Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors (2000) by Hong Sang Soo, quite a declaration of principles. The Internet already existed but was from being what it is now and the circulation of films was by way of VHS cassettes (or tapes, I don’t know how to even call them anymore) or attendance to movie theaters. It was yet early for DVD to become massive (and a few years before they disappeared too as well, such are the times of technology) and movies were mostly released in 35mm prints. Even theatrical releases arrived late and piracy was both remote and primitive. And despite 20 years not meaning a thing, as the Tango song goes, they were too many and yes, they came and went quite fast. Since we are talking about the Jeonju Film Festival, 25 years would be a more accurate span, because this event never skipped an edition, not even in the times of the damned pandemic. But let us leave the Koreans aside for a while and briefly return to history.

Many festivals were born, or became established, around those years. BAFICI did in 1999, so was Rotterdam, which although born in 1972, it was during the mid 90’s where it became an event marked by a word that defined a way of filmmaking: “Independent”. Works by auteurs that were little known or downright unknown back then such as Pedro Costa, James Benning, Bela Tarr, Tsai Ming Liang and many more, became regulars thanks to festivals such as BAFICI, Rotterdam, Jeonju and later on such as FICUNAM in México. Those were golden years where everything seemed new and exciting. Auteurs and entire filmographies could be discovered within a few days, almost always in the presence of the filmmaker being in direct contact with the audience. Adding to this was the apparition of young directors, thanks in great deal to the also young festivals that needed new auteurs. However, everything came and went really fast. In the documentary Chambre 999 (2023), sequel to the mythical Chambre 666 (1982), both present in the festival’s programming, Wim Wenders says that the problem with the appearance of “digital” in filmmaking was in how fast it changed everything, almost without leaving any time to think what was worth keeping from the past. The arrival of digital formats changed not only the way films are shot, but also the way they are released, produced and the ways they move around. This also meant a change in a certain ecology of the festival world.

Almost everything was there to be released and most festivals did. The rise of local talents accompanied all this, programmers flew to other countries to discover films and young directors showed their first and early films in their countries, using local festivals as an international point of departure. But that, as we used to say, also changed. Soon Directors and producers no longer needed the festivals of their countries so foreign programmers could see their films. Links became the way in which movies started to travel so they could be seen and programmed everywhere else in the world by anybody responsible of a festival and starting from there, festivals also started to drift away from the idea of defending a certain kind of cinema and transforming into exhibitions containing a bit of everything. A bit from the so called independent cinema, another bit of mainstream cinema, the old usual auteurs with their new features, etc. Nowadays it is difficult to know what kind of cinema is being defended by the five leading festivals in the world. Cannes, Venice, Berlin and, way in the back, San Sebastián and Locarno could exchange many of their world premieres and nothing ––when not, very little–– would ever change. But here the big problem is Cannes and the conduction of its artistic director Thierry Frémaux. An event that, like a Marvel villain, attempts to take over everything. Not only the careers of several directors were ruined, or changed for the worse, by Cannes, but some critics found themselves facing similar fates. Cannes is the place everybody dreams to go, to be a part of, for being around even if it is to say that everything going on there is wrong (I know this because I was a part of them). Filmmakers, producers, programmers and everyone within the scope of cinema and its industry continue to see Cannes as a goal and a place to aspire for. In a time where filmmakers (directors, producers, technicians) and critics (from the most vulgar up to the most sophisticated) are particularly sensitive towards the injustices happening in the world and the horrors of capitalism (I can’t help but laugh a little when writing this), everybody still wants to be a part of Cannes. No matter the position. It is hard to find critics who would spend their own money to attend a festival like Indielisboa, for instance, or Jeonju itself, but there are not few, in fact there are many who would gladly spend their savings to attend dreamy Cannes. And so, the other festivals languish under the most powerful. If a champion of cinephilia such as Pedro Costa chooses Cannes for the world premiere of a 9 minute short film instead of a festival in his beloved Portugal, what does that leave for other directors? Would it be a solution for all these issues that Costa premieres his films at a Portugal film festival rather than Cannes or Locarno? Perhaps not, but it would be a nice gesture. So nice, that maybe would lead others to imitate it.

As for the critics, it is true that both Cannes and its dumb brother, Venice, still maintain a certain tradition of exclusivity, that is, those who are there covering the event will be the first to see the films that will later play in the rest of the world. Which in fact turn out to be just a handful of those that are programmed. I suggest the following exercise for my colleagues as they read this: try to remember at least five titles from last year’s Un Certain Regard section or many others from the Director’s Fortnight or the Critics’ Week for that matter. Hard to remember, isn’t it? Nanni Moretti mocks Netflix in his latest film, but six months after its world premiere (you know where), Il sol dell’avvenire (2023) became available to watch for the passengers of a French airline, in image conditions far worse than those offered by a Television in any home in the world. The point is that Frémaux does not stand for the purity of films seen at a movie theater, what he stands for is the powerful French industry, of which distributors and theater owners are a big part of. As I write this, that should be a simple and brief introduction to talk about a kind film festival at a small South Korean town. I notice that maybe all this has to do with money. It is a slight suspicion that, perhaps, barely has any grounds.

Small Town

“When you’re growing up in a small town

When you’re growing up in a small town

When you’re growing up in a small town

You say: No one famous ever came from here”.

(Small Town – Lou Reed & John Cale)

In his book Just like starting over – A personal view of the reinvention of the Korean Cinema, recently published by the Korean Film Council (KOFIC), critic and programmer Tony Rayns writes the following about the Jeonju Film Festival:

“Jeonju is an ancient city in the Korean Midwest, cradle of some famous dishes and craftworks, that until recently was not even part of the country’s railroad network. The festival came slightly ahead of the technological advancements by focusing on digital projection and production, but what was the most innovative of all was to locate it in a rural town. Their relative small scale gives the festival some sort of intimacy the attendees tend to enjoy, but the deliberate imbalance between avant-garde cinema and the local population, unmistakably conservative, seems perverse in the best of cases. One year I saw the then director of the festival and the mayor of Jeonju handing out leaflets in the streets, urging the local population to support the festival by buying tickets to see the films.”

When the British use the term “perverse” you have to listen to them, since we know they are experts on the subject. But the idea of a small town having a film festival with an avant-garde programming being “perverse” sounds a bit paternalistic to say the least. Naturally this British colleague refers to past times. Today the city is still small, with a population of little more than 600.000 people, but that counts with four theater complexes only in their downtown area and a theater belonging to the festival that functions all year round. In that theater, previous to the beginning of the festival, La Chimera (2023) was being released and at the end of the festival releases for The Zone of Interest (2023) and Late Night with the Devil (2023) were announced, not bad for a small town theater. The days Rayns speaks about were left in the past a long time ago. One of the biggest problems facing the festival in its latest editions is that tickets are sold out at 70% just a few days short of going out to sale. Something that creates a lot of difficulties to the festival’s organizers and guests, which sometimes do not even have enough tickets for the directors and crew of the films being presented. Since many editions already the festival transformed into a place of gathering for Korean cinephiles whom, taking advantage that the festival dates coincide with a long holiday (which are not that common in Korea as they are in Argentina), go on a pilgrimage to the city to enjoy the programming. Jeonju festival audiences are extremely young, mostly students, who find at the festival an opportunity to enjoy a high quality program, but at the same time come together and spend several days among their film loving peers, watching movies and talking about them. This is, at the end of the day, the true reason behind these sort of events. I wonder which kind of festival Tony Rayns thinks a small city deserves. A Netflix Film Festival perhaps?

I love you, now pay for my film

Now gimme money, (that’s what I want)

That’s what I want, (that’s what I want)

That’s what I want, yeah, (that’s what I want)

That’s what I want, (that’s what I want)

(Money (That’s What I Want) – Berry Gordy & Janie Bradford)

Jeonju’s reputation, at least internationally, is not simply due to its programming or its nice treatment of guests. Although this is something worth highlighting and can be confirmed by those who were lucky enough to attend it in person. While most festivals have it more and more difficult to find its audience –not to mention their programmers, always busy and racing towards uncertain places–, at Jeonju there is still the possibility of chance encounters while going from one theater to the next, chat around and even spend time doing something aside the festival activities. Jeonju’s festival fame is due to something called “Jeonju Cinema Project”. But let us start from the beginning. Shortly after the festival was born, programmers back then had an idea: give financing to filmmakers to produce short films in digital format. Back then, the use of new digital technologies were not yet seen in a good light by directors, but even still the filmmakers that participated in this initiative named “Jeonju Digital Project” almost formed a selection of the best and most renowned auteurs of the last years: Claire Denis, Pedro Costa, Lav Diaz, Jia Zhangke, Tsai Ming Liang, Jean-Marie Straub/Danielle Huillet, and among the Koreans: Hong Sang Soo and Bong Joon Ho. As editions of the festival came and went and with it the rise in the prestige of said short films, the idea took another form: rather than help established artists, why not do the same thing but with young auteurs. And instead of short films, raise the budget and produce a feature film. So it marks the birth of the “Jeonju Cinema Project”. The great difference with this, compared to the funding other festivals tend to offer, is that Jeonju IFF gives them enough financing to make a film, even if it is low budget, rather than the funding offered by other festivals that come attached with several requirements or result in prizes that do not consist of cash, but rather in the form of some kind of service. I remember that not long ago an Argentinian producer asked me, half-jokingly, if I knew of somebody who might need three days of sound editing offered by a renowned director at his company in México, since that was the prize they won with their project. These kind of “prizes” tend to obviously help, but at the same time carry a series of inconveniences that end up delaying the films or end up not being used at all. The Jeonju Cinema Project offers the directors a sum -around 80.000 dollars- and in return asks the filmmakers to have the film ready by next year to have its world premiere at Jeonju film festival. And here is where problems start, or started. Many directors, almost always pushed forward by their producers, once they had their films finished thanks to the Jeonju festival, started to listen to the siren songs of other known and powerful festivals. And so, many of the films made under the support of the Jeonju Cinema Project ended up being screened at Locarno and Berlin, depriving the Koreans of their dream of producing films to secure world premieres. We could argue that this is also useful for Jeonju publicity-wise, and it is true, but what is really left clear is that, as in every walk of life, the most powerful usually get to keep everything. Or at least are the ones to get first dibs. What difference can it make for a film to be released a few months after being seen at a festival in South Korea where it had an attendance of less than a 1000 viewers? None, but the label of “world premiere” continues to be the currency of festivals. In the last two editions of the Berlinale, in its competitive section Encounters, two winning films were produced by the JCP: Samsara (2023) by Lois Patiño and Direct Action (2024) by Ben Russell & Guillaume Cailleau. In many of his presentations and speeches during the festival, Carlo Chatrian, former artistic director of the Berlinale, repeated over and over that the festival world is a community. And a community it is, indeed. One where some live in fancy neighborhoods and others struggle to make rent, but a community nonetheless.

But not all are ungrateful gestures and bad news. This year two of the films produced by the festival did have their world premiere at Jeonju. Nothing in its Place, by Turkish director Burak Çevik, and When Clouds Hide the Shadows, by Chilean director José Luis Torres Leiva, are two absolutely personal works where the filmmakers revisit an historical and personal past that surely will have a long journey around festivals to come. We particularly expect the arrival of Torres Leiva’s film to Argentine cinemas, since in it hovers, in a sensible and emotional manner, the spirit of Rosario Bléfari, whom along with the director’s mother, the film is dedicated to.

This year’s winning project, where Argentinian director Clarisa Navas also participated with her awaited documentary The Prince of Nanawa as well as Canadian filmmaker Blake Williams with I´ve Seen Water, was Serbian director Marta Popivoda with a film titled Body in Plural. A rumor indicates that starting with next year’s edition, those in charge of the festival will only ask the Asian premiere for those films they produce. Raúl Ruiz used to say “I don’t give up, but I get used easily”, and perhaps that’s the best attitude when dealing with film directors and producers.

The Argentine (and Korean) Light

This ain’t no party, this ain’t no disco

This ain’t no fooling around

No time for dancing, or lovey-dovey

I ain’t got time for that now

(Talking Heads – Living during wartime)

What happens in Argentina, and particularly in the world of cinema, is an unavoidable topic of conversation with any foreigner during the run of the festival. Naturally, most barely get to understand what is going on and, even less, what consequences will come out of all this or what can be said to comfort us. On the other hand, the world (even the world of cinema) marches on and, beyond any anger and complain, no one has offered a concrete solution. Argentine politicians seem to have realized that defending cinema does not create a big enough flow of votes and they went to get their pictures taken somewhere else. To think that a letter of support from Alejandro G. Iñarritu can be of any help is naïve at best. But us Argentinians are a bit naïve. For example, another rumor says that the Ventana Sur film market, which for many years was held in Buenos Aires, will move to Uruguay. In Punta del Este, to be specific. Is this true? Is it possible that the love Thierry Frémaux professes to us might not be true or, worse, maybe was a commercial interest? God knows what it can be. For now it is only a rumor, a malicious one like any rumor is. We will see.

The Jeonju festival does not need of speeches and photos when it comes to support Argentine Cinema. Its programming, and not only the one presented this year, but historically (it is enough with reviewing the winners of the past five editions) leave very clear their position regarding Argentine film production: 12 titles, feature and short-length films, were exhibited in different sections of the festival. From experimental works like Materia Vibrante (2024) by Pablo Marín, up to commercial releases such as Puan (2023) by María Alche and Benjamín Naishtat, who is a Jeonju regular, since he not only won with History of Fear (2014), but the festival was a producer on The Movement (2015), going through intimate and personal documentaries such as El Polvo (2023) by Nicolás Torchinsky and even the new film by Matías Piñeiro, Tu me abrasas (2024). All films made with the support of the INCAA, independent and co-productions that make clear something that is as repetitious as it is true: the variety of argentine cinema and their filmmakers.

The triumph of The Major Tones (2023) by Ingrid Pokropek, chosen unanimously by a jury comprised, among many others, by João Pedro Rodrigues, Matías Piñeiro and Canadian actress Deragh Campbell, was the perfect closure for the Argentine participation in the festival.

But let us step into film production in other countries, whom despite not dealing with major economic issues, or maybe they do, but they are very different than the ones their argentine colleagues have to deal with, they also face other issues that are even more difficult to resolve.

In the days previous to the opening of the festival, a Korean film on release, Exhuma (2024), surpassed the 10 million attendances, while another one, The Roundup 4 (2024) approached a million in barely a single day, with obvious possibilities of breaking that mark in the days to come. However, young filmmakers and independent cinema do not seem to be on their finest hour. Not only for lack of screening venues, but also for the little interest these films evoke in the public. An issue that seems to exist everywhere, but in this case, when compared to their more commercial releases, it stands out a lot more.

There were not many movies that could be redeemed from the Festival’s Korean Film Competition. Among them we could mention the remarkable Minmang (2023) by Kim Taeyang, already seen at the Mar del Plata and Toronto film festivals, among many others; Autumn Note (2024), the new solo film by Kim Sol, director of Scattered Night (2019); Silver Apricot (2024) by Jang Man-min; and we could add Lucky Apartment (2024) by Kangyu Garam, presented in another section and not much more beyond that. Current Korean cinema seems unable to escape a certain naturalism and quite tidy production values that looks sometimes a bit like TV.

Argentine filmmakers, as well as their Korean colleagues, are enduring bad times. Something that should make them carry out a complicated yet beautiful task: to register these times through their art. There is the real challenge.

It cannot be any slower.

And it’s a hard, and it’s a hard,

it’s a hard, it’s a hard.

It’s a hard rain’s a-gonna fall

(Bob Dylan – A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall)

Pouring rain changed plans for the festival’s opening and the guest reception, that was going to take place outdoors, had to move to another venue, at a nearby hotel. Rain, always pouring, continued to be present throughout the festival’s run, almost like an unwanted homage to their most glorious guests: director Tsai Ming Liang and actor Lee Kang-shen, who visited the festival to present the up-to-that-moment ten films that comprise the series of films starring the red clothed monk that roams the world walking very slowly, grouped under the title of Walker Series. On request of the director, and in the same way like Fantasy Film Festivals do with their Zombie Walks where participants wear costumes and imitate the way of walking of the living dead, a contest was held where the participants had to imitate the very slow way of walking of the monk portrayed by Lee. It was both exciting and fun to see dozens of youngsters trying to copy the monk’s movements before the very attentive look of Tsai Ming Liang and the advice of Lee Kang-shen. The visit and the homage to the Taiwanese director was completed with the release of a beautiful book -book design in Korea is of a superior level- titled Walker Series, featuring an extensive interview with Tsai, as well as love letters written by major personalities in the film world who admire the Taiwanese director, names such as Adrian Martin, João Pedro Rodrigues and our very own Martín Rejtman, whom in his text remembers the early days of BAFICI, the similitudes between Cropped Head (1992) and Rebels of the Neon God (1992) and that spot called Te Mataré Ramirez. Book publishing in film festivals seems already a gesture of a past long gone and practically lost. Jeonju’s struggle to maintain, with envious quality, such a good and ancient tradition is something to be thankful for.

Past, Present and Future

She said, “You can’t repeat the past.”

I said, “You can’t? What do you mean?

You can’t? Of course you can.”

(Summer Days – Bob Dylan)

One of the festival’s greatest sections bears the name of Cinephile Jeonju, which is precisely dedicated to those cinephiles (that word so frowned upon) that look in the past the answers for the cinema of the future, or simply for re-watch or discover films in new restorations or in beautiful and even more rare projections in film format. But, as it should happen in every good festival, screenings are followed by lectures or classes by film critics and curators. For example, there was the screening of a restored copy of A.K.A. Serial Killer (1975) by Masao Adachi as well as a copy in 35mm, followed by a lecture by academic and critic Go Hirasawa, Adachi’s collaborator, and spoke about the differences in formats, the task of restoration and the complex world within the Japanese director’s revolutionary body of work. Besides, this section counts with a mini-section called Guest Cinephile, which as his name indicates, grants carte blanche to a guest to show and talk about any films he or she wants. This year was the turn of David Marriott, responsible of two companies dedicated to film restoration: Arbelos Films and Canada International Pictures. It is enough to revise the catalogue of these companies to get the picture of what we are talking about. Thanks to their work, and only to give an example, the mythical Satantango (1994) was beautifully restored. Marriott presented three little known and even less seen Canadian films, each belonging to a different decade, as if it was some sort of secret history of Canadian cinema. The titles were: Winter Kept us Warm (1965) by David Secter, which awoke in a young David Cronenberg the idea that it was possible to make films with few resources, The Rubber Gun (1977) the first film by a hero of the VHS generation, such as Allan Moyle, a title that deserves to be seen and known a lot more and, hopefully, with this restoration this becomes a reality and, finally, Hookers on Davie (1984) by Janes Cole and Holly Dale, a documentary about sexual workers in the title street in Vancouver, a work that belongs in the great tradition of Canadian documentary cinema, which features Ron Mann among their acknowledgements, and describes in a painful and sensitive manner a world now disappeared but was, among other things, the point of departure for social struggles that continue today. The presentations by David Marriott are a true luxury where he displays not only his knowledge, but also his enthusiasm for cinema and its history. Marriott, like many characters that improve the quality of the festivals (and the world in general), is an anonymous hero whom with his work and dedication helps keeping alive the most unknown corners of cinema history.

Post-Scriptum (Clarification and Send-Off)

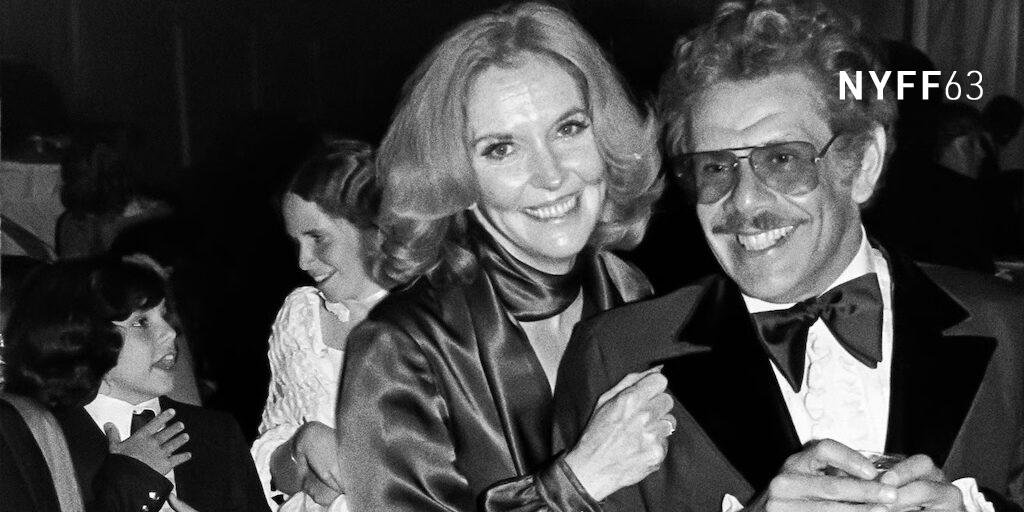

After the release of Day by Night (1973), Godard complained to Truffaut that he did not show in the film he was dating the protagonist, the beautiful and talented Jacqueline Bisset. Since I don’t want Jean-Luc’s ghost to haunt me in my dreams, I’m in the obligation of clarify that one of Jeonju festival programmers, Sung Moon (known as Luna for her Spanish-speaking friends), is the person I’m sentimentally joined with since 2012. Being the husband of the programmer, since she took that position for quite some years, is the title I carry with most pride since I partake in this strange craft. Therefore, my opinions about her festival must be heard with precaution. And also because the Jeonju festival takes me back to those days where festivals, and now I’m speaking of Argentina, knew how to be places and moments of gathering and happiness. I do remember.