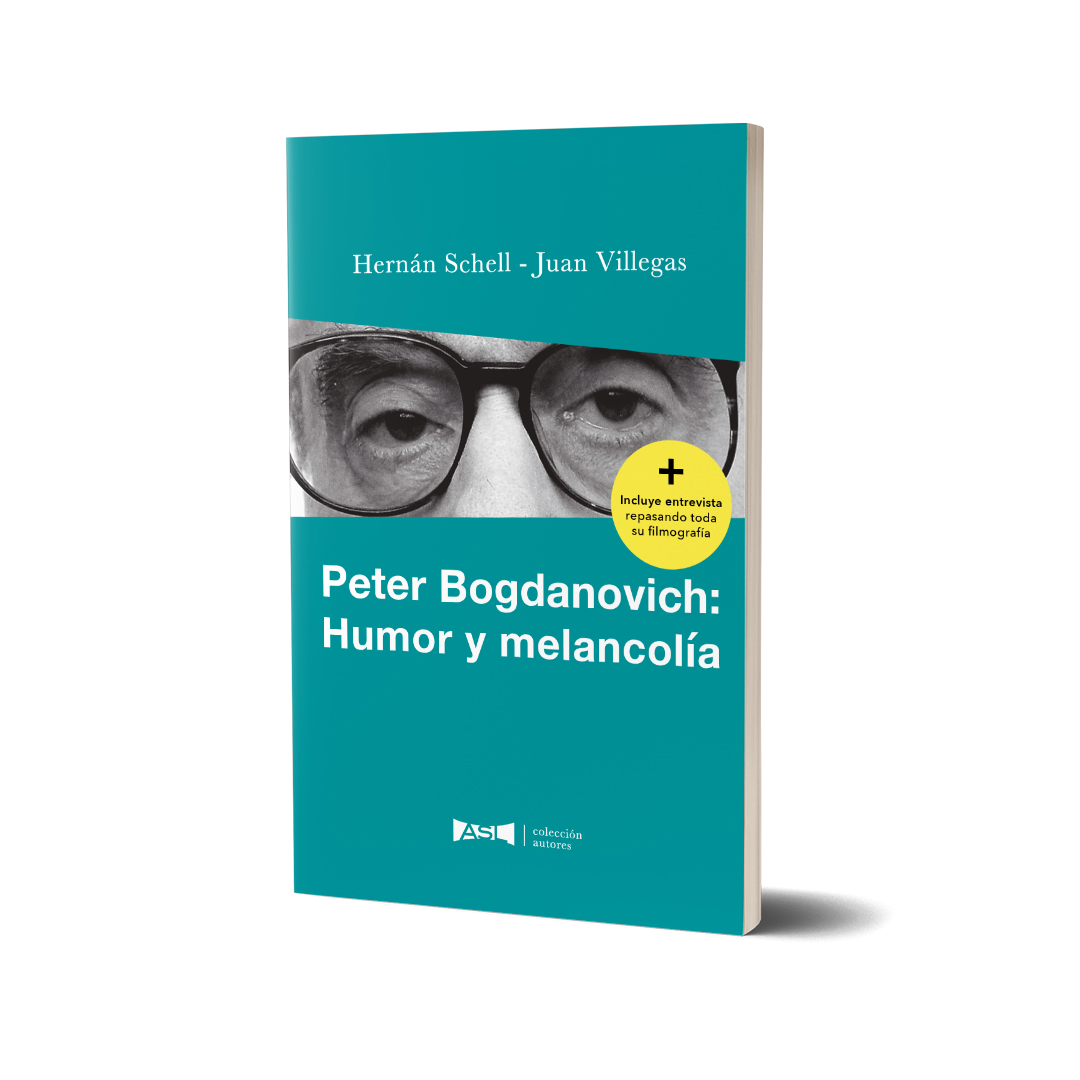

Book Title: Peter Bogdanovich: Humor and Melancholy

Author: Hernan Schell, Juan Villegas

Language: Spanish

Publisher: ASL Ediciones

Collection: Auteurs

ISBN: 9789878702704

Buenos Aires, 2019

250 pages

THE THING CALLED LOVE

American Nobility

There is a kind of film that only Americans know how to make well. It is not about a particular genre or subject matter. Is something hard to define, an air of family that certain kind of movies tend to have. They are tender and sensitive, but shy and discreet; emotional to the verge of tears and at the same time funny and light-hearted; the character’s conflicts seem simple and flat, while they have a hint of depth which is never declaimed; they have no qualms in taking upon them the most ancient codes of the film language, but at the same time they breathe freedom and seem to be made from conviction, without compromising to anybody. The characteristic that better defines this kind of movies is nobility. It is not a matter of whether noble movies cannot be made outside the United States, but there is a kind of nobility that can only be American. The rest of us can only emulate it and maybe approach it, but there is a tone, a way of configuring the fictional world that can only be achieved in American cinema. The Thing Called Love is one of those films.

However, a great injustice surrounds the critical appreciation about it, making it one of Bogdanovich’s least acknowledged films. It performed less than expected at the box office, way under its budget. Once again, just like in mid-70s, Bogdanovich linked three box office bombs in a row, if we add to this the meager results of his prior two pictures: Noises Off… and Texasville. But there is a huge difference. Bogdanovich’s failures in early 90s found him at his finest creative moment. His movies reached an unheard maturity and a comprehension of the world and its people, sustained in a spirit of lightness and freedom. But this time around commercial failure, which in American film culture is punished with contempt and oblivion, also met tragedy.

River Phoenix passed away on October 31, 1993, two months after the film’s release. His death cast a shadow over any judgment the film could have and relegated it to a cursed spot of which it was hard to get out of. In January 1994, in a rather despicable review, Roger Ebert wrote: “Of course you go to River Phoenix’s last finished film in a certain state of mind (…) but there are more pragmatic thoughts, too: Will his performance reveal signs of the drug use that ended his life? Or will this farewell performance show him at the top of his form? (…) In Phoenix’s first scene, it is obvious he’s in trouble. The rest of the movie only confirms it, making “The Thing Called Love” a painful experience for anyone who remembers him in good health. He looks ill – thin, sallow, listless. His eyes are directed mostly at the ground. He cannot meet the camera, or the eyes of the other actors. It is sometimes difficult to understand his dialogue. Even worse, there is no energy in the dialogue, no conviction that he cares about what he is saying. (…) The world was shocked when Phoenix overdosed, but the people working on this film should not have been. (…) So perhaps no one could have saved Phoenix. But this performance in this movie should have been seen by someone as a cry for help. (…)at the center of the film is an actor whose mind and heart are far, far away, and he is like a black hole, consuming light and energy. He’s running on empty. Sometimes there are even scenes where you can sense the other actors scrutinizing Phoenix in a certain way, or urging him, with their tones of voice, to an energy level he cannot match. It is all very sad.” Would have Ebert say the same thing of River Phoenix’s performance should he not died a few months after finishing the film? We are sure that he would not. But maybe the larger issue here is not so much that he was cruel with someone who cannot defend himself, or even that he throws a veiled accusation towards all those working on the film of being an accessory to his death. The larger issue is that it is a lie. Phoenix’s performance is so intense, subtle and committed like every single one in his brief but extraordinary body of work. It is true that there is, in several scenes, a dark tormented side. But was not that always part of his style, somehow verifiable in movies so different such as Explorers, My Own Private Idaho, Running on Empty or The Mosquito Coast? In fact, we can even say that if there is something new in Phoenix’s performance, when comparing it to his prior work, is an explosion, light-hearted and full of life, which appears especially in the musical moments.

Anyhow, Phoenix’s character is not the lead in this film; the major protagonist is Samantha Mathis. In fact, Bogdanovich has told that he believed Phoenix was not going to accept the part, since he was a full-fledged star despite his youth, and it was clear the story was told from Mathis’ character’s point of view. But Phoenix dreamt of singing in a movie, and here he was given the chance. The entire weight of the narrative falls on Mathis’ shoulders; her Miranda Presley, her unforgettable Miranda Presley, is the moral and energetic drive of the story. And starting from her character ––her construction, her journey and her actions––, the movie emerges as a delicate and concealed feminist manifesto. It is one of the most surprising aspects that come up upon a second watch, because it seems to have been ignored both at the time of its release as well in further readings of the film. It is the story of a lone woman, who has a dream, a deep desire and is willing to fight to make it come true. It is also the story of her love for James, but a love always subordinate to her own convictions. Already in one of the first scenes, when she is settling at the hotel, a shot of the interior of her suitcase gives us a glimpse. What we see is a Johnny Cash cassette, another one of Elvis, a book of poems by Robert Graves, another one by Robert Frost, a copy of A Room of One’s Own by Virginia Woolf and a Time magazine with this inscription on its cover: God and Women. Cash and Presley are canonical musical inspirations. The former is perhaps the maximum idol of country music, a fundamental subject matter in the film; the latter, more associated to Rock and Roll, although not removed from the great country music tradition, is going to be a referenced and revered farther down the line. Frost and Graves, two poets especially concerned about rhymes, anticipate Miranda’s desire to write songs that work and provoke emotions. The Time cover is more enigmatic and will only allow one posterior interpretation, retrospectively, when we hear the song with which Miranda finally achieves everything to go along her desires. As for Woolf’s book, an unquestioned feminist milestone, there is not much more to comment.

But the film’s feminism is not only anchored in hints and references. After the scene when both are rejected for the audition, Miranda confronts and reproaches him about using her as an excuse without her permission. It is easy to attribute Miranda’s tough yet sweetly confident attitude to the tradition of the strong yet decisive Hawksian women, given the absolute devotion of the director of The Thing Called Love to the Red River filmmaker. But there is something more: Bogdanovich holds himself accountable for his place in time and dares to present a modern free woman. If he does so without any manicheisms it is because his style is never emphasized. If he does so without lecturing and without the need of handing out politically correct speeches is because he knows that what is important is the truth of his characters and the emotions these can transmit and not so much their opinions or ideologies. However, a feminist force is imposing itself. A couple of minutes later, already at the dance sequence, she confronts James once again to admit what he is feeling. She tells him firmly and bravely. Then she goes to seek Kyle, because Miranda is noble (like the movie itself) and feels that, if she came to the party with Kyle and is leaving with James, he owes the former an explanation. Kyle asks if she is asking for permission. Miranda says no, without covering up her feeling offended by the question.

Bogdanovich is a director that seems not to have a defined visual style. We believe this perception to be wrong. There are stylistic resources all over his filmography, but his formal obsessions become invisible into an apparently inattentive look, generating the false sensation of a conventional openness. In The Thing Called Love, Bogdanovich constructs the best scenes in the film resorting, as he sees fit to each situation, to the two most characteristic formal devices in his body of work: unbroken shots and editing between stares. Of the former, there is a good example in the scene where Miranda takes away make-up from Linda Lue and we see how the friendship between both women seems to strengthen. The correspondence between the movement of the camera (slow, permanent, yet almost imperceptible) and that of the characters is so precise, that one has the strange feeling that it could not have been shot in any other way. Nonetheless, we know is not like that. Bogdanovich decides not to cut and privilege the continuity of the dialogue without any interruptions. But he also decides to start the shot allowing all the room to be seen and end it in a tight framing on her faces. However, in other circumstances, he will opt for fragmentation. And we also feel that course of action to be right and inevitable. In the wonderful scene where the four protagonists make their respective tryouts at the Bluebird Café. There are sixty shots in only five minutes, in which we understand a lot of things and sense so many others, even though there is practically no dialogue. Bogdanovich achieves this through the crossed stares between the different characters and the adequate choice of shot sizes for each case. A natural continuity is appreciated, in which the comprehension of space is perfect and establishes not just the distance between characters but the feelings every one of them generate on each other. Is curious, because when Bogdanovich opts for fragmentation, the sensation he produces is one of continuity. In the other hand, when he opts for the continuity of an unbroken shot, the memory we keep is that of a fragmentation.

Fragment of the book “Bogdanovich: Humor and Melancholy”