In this column I want to do the following exercise: go back to seeing the films that marked my childhood/youth to evoke them and see how they resonate in these times. Not only in cinematographic terms, if they were “good” or “bad” (I care less about that sentence every time) but also what things I learned in them that were lasting for me.

I was a child in the 1960s. The period of intense cinema consumption took place between January and March in Capilla del Monte, Córdoba, where part of my paternal family lived and where I systematically vacationed every year. Capilla had a single movie theater, located on the same street where I lived but a couple of blocks down, closer to the center and its roofed street where one strolled before dinner. On Mondays I would get up and, before going out to play with my friends, I would go down the slope of Dean Funes Street to see the renewal of the movie posters that covered each of the doors of the cinema entrance and announced the weekly programming. I was excited if there were horror or science fiction movies and frustrated when the poster hinted at adult drama or romances.

However, of all the films I saw in Capilla del Monte, the one I remember the most, the one that made the most powerful impression on me, was not a fantastic work: it was The Graduate, by Mike Nichols, the recognition of Dustin Hoffman and the musical duo Simon & Garfunkel. The Graduate is from 1967, which means I probably saw it in the summer of 1969, at which time I was 13 years old. Childhood was about to end and a tortuous and terrible time dominated by hormones was about to begin. The combination of an effervescence about to hatch and Anne Bancroft was enhanced in an incomparable way. She is at the center of the solar system of my memories in her in black underwear. On the outskirts, the songs by Paul Simon, the final scene of the church and the dialogue in which a friend of the father assures Ben, the character played by Hoffman, that the future is summed up in one word: “plastics”.

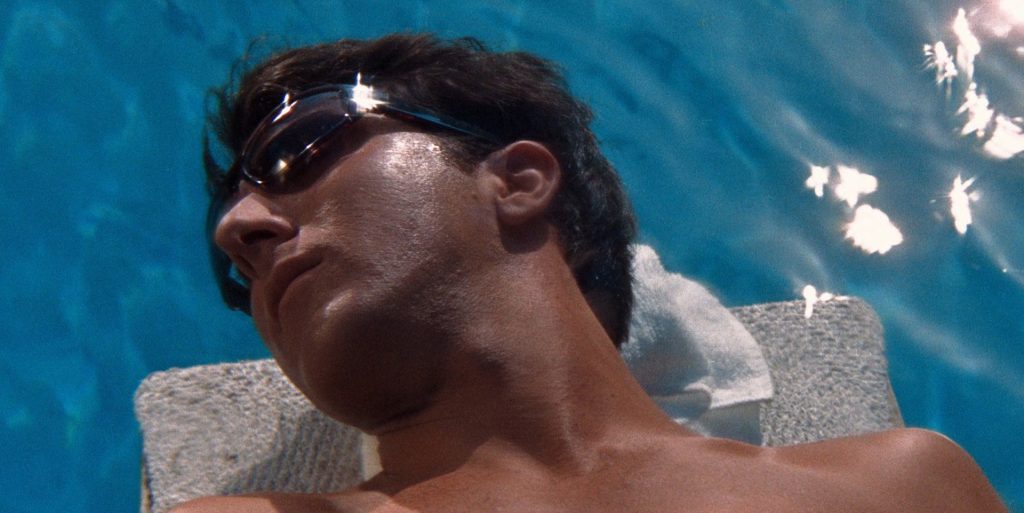

Seen more than half a century later, The Graduate reveals several surprises. The story is simple and divides the film in two. Ben Braddock (Dustin Hoffman) graduates and returns to his parents’ home. He is about to turn 20 and the world of adults is alien and false to him. His parents welcome him and give him a welcome party. Among the adults a friend of the parents stands out, Mrs. Robinson, who is conjuncturally alone. She decides to seduce him. After some resistance from Ben, she succeeds and an almost exclusively sexual relationship between the two of them begins.

The first part of the film is dominated by Mrs. Robinson, the second part by her daughter, Elaine (Katharine Ross). It is 1967, the Beatles have barely had four years revolutionizing customs, the new generation breaks patterns and prejudices. The Graduate shows that: in the first part, that of Mrs. Robinson, adults predominate in closed, vicious, sordid and dark spaces. The second, dominated by Elaine, abandons that world and looks for a more open, young and vital one. Love triumphs over sex, the young over the old, the sincere over the clandestine. The polarity shown in the film metaphorically represents the revolution that is taking place: young people come and change the world, for the better. For the better?

The most interesting thing about reviewing Mike Nichols’ film half a century later is precisely to relativize that polarity.

Firstly, that my memories have prioritized Mrs. Robinson was neither casual nor personal (in fact, there is no song for Elaine, but “Mrs Robinson” became a hit for Simon & Garfunkel). Anne Bancroft’s presence on the screen, her character’s personality, the way a woman is sexually active and in the midst of the seduction process seem more revolutionary than the informality and sincerity that youth seems to bring. It is remarkable to note that Bancroft was just 36 years old at the time of the film. A few lighter strands (are they still saying “highlights”?) officiate perceptively like gray hair, and her firm and confident attitude adds years and maturity to an incredible face and a spectacular body. The tension and appeal of this first part (which lasts almost an hour) far exceed 40′ dominated by the character played by Katharine, beautiful but languid, fresh but deserotized.

Secondly, the last scene of The Graduate redefines the film in a clear way. Recall that Elaine is at the altar about to marry another candidate, Ben comes running and panting to the church, causes a scandal and manages to escape with her. They get on a bus, sit on the last seat, finally together and with all the future ahead.

Mike Nichols does not make them kiss or hug. They look at each other, smile, stop smiling, continue in silence, and the shot continues, beyond what is necessary. The song that opens the film, “The sounds of silence”, plays again, a perfect song about loneliness and alienation. The confusion is total. It is not a happy ending. Miss Robinson, beautiful and pure, will eventually become Mrs. Robinson. The wheel turns again.