JUSTICE WAS SERVED

It is impossible to avoid a comparison between The Trial and Argentina, 1985. Let us begin with the conclusion: The Trial is better: it is a serious film, without any sloppiness or capricious interpretations of history and does not try to please the audience with resources of the most conventional filmmaking. Argentina, 1985 was released with a great roar, but the interest for it has dwindled after its failed excursion to Hollywood and it is not a film destined to last long past its theatrical run. On the other hand, The Trial has its future assured as the cinematic document of an important event.

The Trial is what it claims to be: a three hour summary of the trial of the first three military juntas of the last military dictatorship, which took place during Alfonsín’s administration between April and December 1985. It is a sober and very arduous work, which does not stand away from the 530 hours officially recorded in court. Naturally, it is not the trial itself, not even a miniaturized version, since the selection and editing of the scenes and shots are inseparable from an outlook and a narration. Other filmmakers could have made very different movies from the same material. It is also convenient to stand out that (in the same way Argentina, 1985 does), the movie is locked up between a prologue and an epilogue that make clear that the trial was the first step, taken forty years ago, of a fight that goes on to this day so all the guilty parties of crimes committed during the dictatorship end up imprisoned, although the original intention of the trial was not that one.

But beyond that frame of mind that could be defined as militant and is part of a different discussion, the film is a window looking out to a dark period of Argentine history. Behind the mise-en-scene trial movies had us accustomed to, behind each testimony, each intervention of the judges, prosecutors and defense attorneys or the reverse shots on the audience, we can observe the state of this discussion in the Argentinian society of that time. The film’s narrative construction, planned as a rhetorical battle between the plaintiff and the defense is shattering as a demonstration of the prosecution’s main thesis: that the crimes committed by the members of the juntas and their subordinates constituted both a systematical plan and a legal, political and human aberration that do not admit any possible justification and deserves a prison sentence.

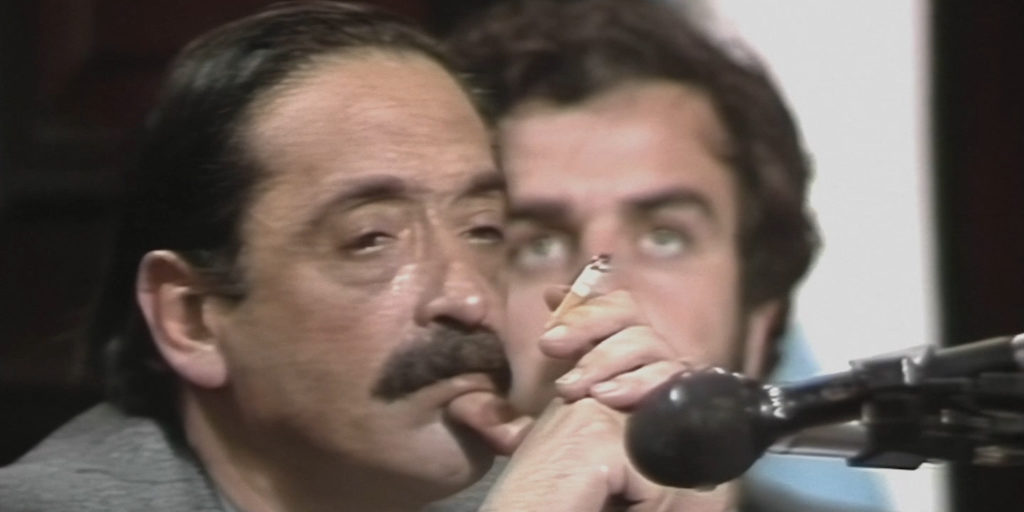

In 1985 the participants of the military government and their minions still thought of themselves as heroes of a war they won and they were being judged without any rights. That affirmation is part of Massera’s statement and the reasoning of several defense attorneys (each one of the accused were represented by different lawyers). The overwhelming military superiority of one side over the other and that it could have been resolved within the law, shows that the hypothesis for the war was only an excuse to cover a gigantic operative of legal repression. That fallacious argument, whose echoes still sound off today, went hand in hand with another: that the constitutional government circumstantially led by Ítalo Lúder was the one that ordered the assassination of members in guerrilla groups, when the corresponding decree said nothing about annihilating people. In any case, no one can sustain that the kidnapping, torture, hiding of corpses, the assassination of prisoners, the subtraction of babies and plain simple robbery could be part of a decree emitted by the Executive Branch during democracy. However, that is what can be heard from the defense attorneys: that the war they unleashed gave them full right to commit every crime that the Geneva Convention prohibits. One of the defense attorneys even went as far as to justify the looting and appropriation of property owned by the murdered and disappeared as legitimate spoils of war.

Both the pages of the Nunca Más and the images of the trial prevent to sustain the hypothesis of the dirty war when what was being put on trial was a series of atrocious crimes committed against defenseless detainees. Neither was to attribute those abhorrent actions to excesses of the subordinate personnel: the accusation was very conclusive when showing that the crimes were committed in military facilities all over the country and, as Patricia Derian, undersecretary for human rights to President Carter, arguments before the judges, it is impossible that within a corps of military discipline under a dictatorship, the high command ignored what was happening at such scale. On the contrary, the same military code of operations held every one of them responsible even if they insisted on deny what happened. Both the chilling statements from the surviving victims and the relatives of those assassinated are eloquent enough in the film so as to have a clear idea of what happened in the detention centers as well as the chain of accomplices associated to a corporate silence when facing the requests of information from citizens, human rights lawyers (who had disappeared of their own) and foreign governments.

Besides the arguments of Lúder’s orders, the dirty war and the ignorance of the commanders about doing what they did as following orders, the defense tried to show that the victims were members of terrorist organizations and, therefore, guilty of other crimes, which in some way would diminish the guilt of the executioners. There (and, on a personal note, this was something I ignored about the trial) was the decisive intervention of the judges, that refused to accept that witnesses were asked about their political allegiances or activities, the same as with victims’ families. In this way, they thwarted a maneuver that tended to treat the tortured, the murdered, the disappeared and their assassins like equals. It was a wise move from the Chamber that, to the fury of the defense attorneys who tried to turn the tide in their favor, invoked the argument that the culpability of the victims was not under trial. About this, it is fit to remember that Alfonsín always thought that the surviving heads of armed organizations also had to be indicted as terrorists, that is, to apply onto them the legal procedure the military replaced with their own clandestine terrorism. And that allows us to return to a trite subject, related to the always reviled and never formulated “Theory of the Two Demons”. Facing the theory that the military government and the terrorist organizations were fighting a war, it would be fair to say that it was not like that but, on the other hand, each one of the sides were waging their own war against constitutional order, against the Republic and, definitively, against the people, mostly unaware of the purposes from both sides. The military were not enemies of the guerrilla and these were not the enemies of the military, simply they were an obstacle to their plans.

The darkest attempt in creating confusion had to do with the stories about what happened at ESMA and with Massera’s plan of rising to power through an election, an endeavor for which he utilized a group of prisoners while others were thrown alive from Navy aircrafts. This horror within the horror is one of the most sinister chapters of what occurred during those years. The film insinuates something of what happened there, when the defense attorneys tried to establish a collaboration with the illegally detained.

Lastly, although The Trial reveals the horror within the extermination centers and shows the strategies from the prosecution and the defense, it does not say a word about the sentences. After announcing them in a superimposed text during the end credits, fragments are heard, superposed over each other of the lecture of the ruling by Leon Arslanian, president of the tribunal. Although attorney Strassera requested nine life sentences, only two of the indicted received that sentence: Videla and Massera. There was, besides, four acquittals. The difference between sentences is due to the different accumulation of offenses during the period in which each junta held power, the difference between criminal procedures among the three armed forces and the gathered evidence. In Argentina, 1985 there is a moment in which someone asks Strassera what is going to happen should they not find evidence, to which the attorney answers “If there’s no evidence, we’ll accordingly request the acquittal.” That The Trial ends with a superposition of voices that seem to scratch out the fact there were minor sentences and acquittals is, in my opinion, another concession to the right for ideology, ever a symbol of the many registered recently. But those acquittals were an indirect proof that the trial of the juntas, besides being insightful, was fair and honored Argentinian justice.

![]()

(Argentina, Italy, France, Norway, 2023)

Script, production, direction: Ulises de la Orden. Lenght: 177 minutos.