Life is not a dream, but it might be one.

Novalis, Fragments

If the early Scandinavian reaction to Hollywood cinema (Stiller, Dreyer et al.) can be characterized as a tension between epigonism and autonomy, the German position should be defined taking into account, and quite inexorably ––a very Germanic adjective, on the other hand––, the particular characteristics of that which is German related to the western tradition. To summarize it into a signature image, we will say that the Germanic is a point of that which is Western-European that is found since forever in a tug-of-war between their Mediterranean wishes and their hyperborean reality. On one hand, there is the luminosity, the order, the spirit of system, the operative willingness; on the other hand, that which is dark, the foggy, and the disorder of a world that craves for light and finds darkness every step of the way. The spirit of system goes back, bartering into solipsism every time that which is German hits head-first with history, which no people has confused or matched so much with reality, in toto.

Germany is self-aware of being and is cyclically remembered as the last place the Roman Empire conquered and wanted for itself, leaving the rest to the manes of the Terra Incognita, to the Last Thule of the unknowable, the undecipherable and ––let’s be frank–– the irretrievable. No people entered modernity provided with a symmetrical contempt for the very thing it helped to coin: History as a strict science.

Another image can come to our aid for understanding. In E.T.A. Hoffmann’s biography we are told that in his early youth he attended Kant’s classes at Konigsberg… and was bored by them. We have to remember that from that tedium the modern fantastic short story was born, the horror short story, that departure from imperative reasoning and deduced a priori towards the “gothic” swamp of a dark age, but also valued, symmetrically, as luminous.

This duality rose in the Germany of back then, immersed between a spirit of system and a confusing fascinating nostalgia for a traditional Middle Age, halfway historical and halfway dreamed. From that dream, from that will of losing itself, deleteriously and narcotically, into a sublime remote ideal, an exclusively Germanic form was born: romanticism. On one hand, Kant and Hegel; on the other hand, Hoffmann, Novalis, Von Kleist, Holderlin. On one hand, the tutelary and aulic shadow of Goethe; on the other hand, schopenhauerian pessimism and the delectably painted abysses by Caspar David Friedrich. On one hand, the Aufklarung ––German version of “illuminism”––, with their maps reasoned in categories, judgments and limits to those judgments; on the other hand, the temptation for the abyss, the castle in ruins, the crack, the breech, the vertigo, the jump into the vacuum.

Order and system in one hand, dream and delusion in the other; and all on account of what? Because the German is aware of being a participant in that double world, that double universe turned destiny between the Mediterranean and the Nordic. A destiny that, as centuries went by, tried to resolve with secessions and unions, running away to the autonomous-absolute and returning cyclically seeking for shelter in a bigger unit, lost and recovered in a nostalgic dream. Luther and Goethe, on one hand, and Novalis and Holderlin on the other hand, are central and cyclical points in this argument: reform, separatism, division, secession; but also nostalgia for the unity, the recovery of that which was lost, a yearning for mediterraneanity

If the concept of “course and resource” coined by Giambattista Vico is not enough for us to reason about these subjects or, in any case, awakes the need of an image that complements it emblematically as a support for its contemporary recapture, we propose this variant of the definition of “modernity” coined by Baudelaire.

Starting with modern times, a division can be found in the West, regarding human events between what we can characterize as a “timely impulse” and a tendency to that which is permanent, that which is eternal. Something spread into a space not only geographical, but in that which Konrad Lorenz defined as “territoriality”. That spiritual-emotional propriety zone that, on occasion, history reflects in a determined judicial-political stratum.

Every renascent apparition of a determined particularism is ––and our times prove it daily with shocking clarity–– the detachment in the historical field of a world constructed in the western imaginary beyond the maps and the political ups and downs. That which our forefathers called ecumene, that world ––and place–– known and acknowledged by determined characteristics, but not through a fatalist determinism, but a willingness to set roots that only the mythical resource can make us apprehend, even so tentatively.

That dichotomy, sometimes brutal and aggressive, sometimes tender and radiant, took place in Germany more than in any other place. After the Italian Renaissance, no people in modernity dedicated themselves with such skill and stubbornness to the task of recovering the Greeks and Romans; from philology up to the vast philosophical systems. Archeology is a Germanic invention, or almost. Since the disinterring of the ruins of Troy, over to the meticulous study of the Roman Empire, until creating some sort of replacement for the Greek tragedy through the Wagnerian total-work-of-art; all those forms and manners were displayed in the German world, but there was a fundamental difference that enrichens what we wrote down. That difference was the Habsburgian Empire, later known as Austrian-Hungarian. A Germanic creation, but a Germanic-Catholic one, with a foot set, soundly and visibly, on the Mediterranean, and with a conglomerate of nations, ethnic groups and particularisms resolved into an ecumenical will.

Around 1918 ––after the destruction of the Empire––, with the rise of Hollywood cinema, an early and fundamental articulation appears for the ulterior development of this art, its canonic display and its consequential occupation of cultural power. (1) A power that, acknowledged or not by previous forms of thought and poetics, becomes from that moment in an axis for cultural decisions; closing in the process the permanent deliberative state of the previous romantic colloquium. The fact that “decisionism” was reflected in the historical display is something that, for the time being, we are not interested in discussing, at least not in this place…

A German educated at Heidelberg in art, history and literature, and a Viennese trained in architecture appear in such circumstances. Friedrich Wilhelm Plumpe (1888-1931) ––renamed for cinema as Murnau–– and Fritz Lang (1890-1976) are the ones charged with the task of reflecting in their films the first self-conscious registry of the concept of cinema in Europe. Also appearing in them, and in an immediate way, the constant dualities priorly enunciated: fantasy and system, order and chaos, “Gothicism” and darkness. Both of them separate, punctually, precisely and with a huge decisionist will, German cinema from what can be called “the Caligari syndrome”. That expressionist “pictorialism” wax museum that threatened to become “style”, either as a formal autonomy or as a style of aesthetic particularism.

Without Murnau and Lang the Germanic cinema would have fallen in a teratological inmovilist swamp, in the paralysis of a return ––by other means–– to the Lumiere-Melies cinematographer but in a night key; in a gallery of dolls exhibited through filmic reproduction.

The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari (1920) can be understood through this hermeneutical resource. Caligari and Cesare, his automaton, would represent some sort of possible destiny for German cinema: a charlatan and his atrocious doll exhibited among cardboards of a confusing nightmarish iconography; an exhibitor of atrocities and his puppet which, through a flow of shady hypnotism, is led to commit monstrous crimes. That these crossroads were finally “resolved” in an asylum for the insane, with Cesare as a patient and Caligari as a psychiatrist, (2) conform a circle of perfect indecision; a limbo of nocturnal geometry.

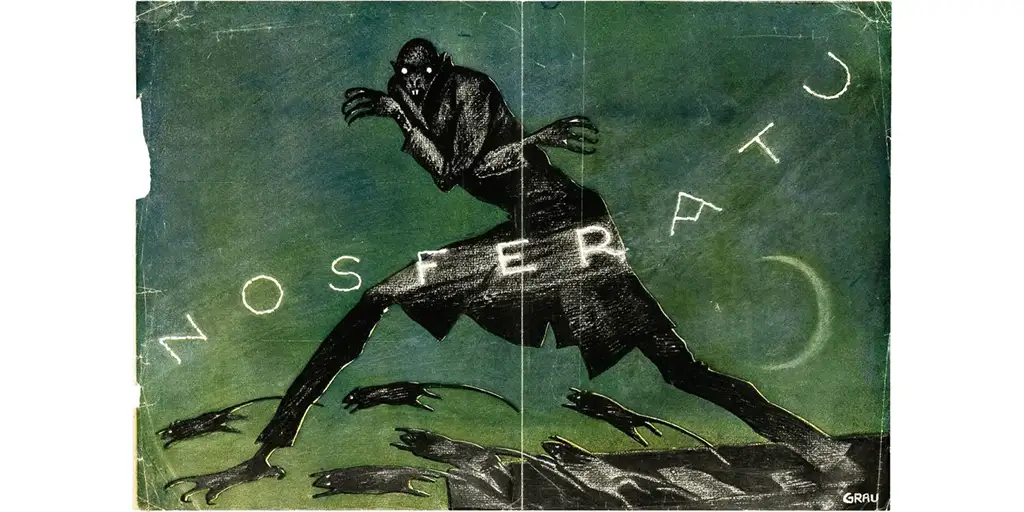

In Nosferatu (1922), Murnau chooses a “horror symphony” ––as he subtitled it––, and if a symphony consists of four movements that are variations of themes or recurrent motifs, (3) we can, by simple arithmetic, realize about the auteur’s stylistic will. These are: everyday life (the romance between Ellen and Hutter); journey into the world of the dead and ghosts or, if you will, the hero’s descent into hell; symmetrical journey of the vampire and the following plague; to arrive, finally, at Ellen’s sacrifice with her guaranteed resurrection, or death and transfiguration.

We can also understand it the following way: an introduction in the manner of an Allegro con brio; (4) second movement: Andante, with the journey, Hutter’s walk up to Dracula’s-Nosferatu’s castle; (5) third movement: Poco Allegretto, (6) plague, chaos, death; finale: once again an Allegro, this time without exuberance, depicting Ellen’s sacrifice, death and atonement.

We have taken the taxonomy of the third of Brahms’ symphonies, for many both the epitome and the conclusion of German musical romanticism. With a Mahler symphony it would no longer work, neither would with one of Beethoven or Schubert. The first analogy is too tardy, the second is too premature. (7)

Above the musical analogies, Nosferatu is the reestablishment of classical unity, of the apollonian decisionism to get out of the museum dionysism or greenhouse represented by Caligari. There is no more exhibition but representation; not anymore a circular delight, but a straight line leading to what Greeks called, in its tragedy, the anagnorisis. That is, an acknowledgement of the hero’s or heroine’s precarious situation. Such acknowledgement implies an atonement, a catharsis, a discharge or purge of the vertiginous sublimity to which we have been led. Without that discharge, art renounces to its purpose and takes shelter ––as in Caligari’s ending–– in the technical-scientific knowledge. The “now I know how I can cure him”, said by Caligari turned into a psychiatrist in the film’s final sequence, shows a renouncement of the art turned into an intermediate vicar of science; an abjuration of its judgment and territoriality, leaving it in the hands of the technical procedure. (8)

Murnau, on the contrary, seeks to submerge into the “destructive element of life” (9) and, finally, on account of the resurgence of some spiritual potentiality that will pay the subsequent time passing of the human adventure. (10)

There is in Murnau a “vatican” bias exploring the nocturnal side of life, and a bias or epic manner unfolding in the chiaroscuro of everyday life. The first is depicted in films such as Journey into the Night (1921), Phantom (1922, one of the greatest films of all time, and sadly one of the least frequented, even by those who imagine themselves as professional “Murnaunians”) and The Haunted Castle (1921).

The second is displayed in films such as The Last Laugh (1924), Tartuffe (1925), and those made in Hollywood such as Sunrise (1927), City Girl (1930) and Tabu: A Story of the Seven Seas (1931). The synthesis or the intertwining happen in Faust (1926), his last German film. Here nocturnality and charioscuro are resolved into a tradition that harmonizes ––as a bridge–– both of those extreme forms. Although Tabu left us with one of the most inextricable enigmas of contemporary art: which road or path would the auteur have taken after the discovery of the “primitive” confined to tragic categories, not yet experimented or, in any case, lived differently by an external tradition.

But his death, shortly after the release of the film, created a breach as huge as the one created by his fellow countryman, Novalis, dead shortly after writing his essay, emblematically titled, Europe or the Christianity. A text that together with Von Kleist’s “On the Marionette Theatre” conform the epitome of German romanticism.

Nosferatu is based on the novel “Dracula” by Bram Stoker; or you can also say it was “inspired from”, given that the first part of the film follows almost faithfully the story laid by this author. But the second half, especially the ending, is way more diverse. It is proven then ––1922–– that the concept of cinema couldn’t just portray, reproduce if you will, a prior literary text. Even more so when this was portraying a mythic variation of a bigger myth; by this we mean a mythologeme. Therefore, it had to create at the same time a new mythologeme.

Therefore, Nosferatu is the first European reflection, already complete, of the concept of cinema. It is not a minor occurrence that this first, and for a long time only, transatlantic avatar of the concept of cinema was produced in German imaginary ––rather than geographic–– territory.

If ––as we have affirmed––, “cinema settles the score with romanticism”, a last link to that first romanticism needed to be articulated and through a configuration integrated to cinema and its concept. Therefore, it could be judged or be characterized in toto as the vulgarly known “expressionist” period. Now that its own literary ductus, or rather the poetical-theatrical-pictorical from which, give or take, resulted in one for the cinema ––though taking another path and turn–– was an extreme or last moment of the first German romanticism, or “historical romanticism”.

It is not just due to the appendicular extension of the sets and framing as configuration of a character and a psychology, or an existential type that “expressionism” can be described as. But as the ultima ratio the romantic soul could and should have manifested through that movement by an American “medium” and transatlantic to its European spirit. Especially when the full setting into motion of the total mobilization was already effectuated; and, a fortiori, when Germany itself has been the most wronged and damaged in that historical-spiritual trance.

This reveals another connection. Because that “medium”, the concept of cinema, has been operatively instrumented shortly before by someone like Griffith, also born in a territoriality ––the Confederate States of America–– defeated by the display of total mobilization.

The subtitle, or motto, “A Symphony of Horror”, in Nosferatu is not a mere presentation detail. As we have said, Murnau himself had to support himself in a very German “piece of information” to display his film; given that it can be divided quite exactly into the four classical movements of a symphony.

It has been speculated that some of the changes made in Nosferatu from the novel by Bram Stoker were due to the homosexual condition of its director. That Ellen’s final sacrifice ––“passively” stopping the vampire until, with the arrival of dawn, he’s destroyed in his condition as such––symmetrizes the emotional state of Murnau himself regarding his sexuality.

We think it is not just a typical psychological dissolution, but an even more typical reconstruction a posteriori. With George Cukor this will be taken to an absurd edge. The condition of an artist, or public person in general terms, is discovered post factum, and once this is done, it is looked out for appendicular extensions in every gesture, sign, step and whisper he has effected or disclosed as a mere rigid connection to his sexuality.

This reasoning forgets the first and foremost. The genius ––male or female of any sexual inclination–– doesn’t live in the same order of values than the rest; he/she does share, as a subset, tangential and even radial planes in the social sense, as well as the economical, political, cultural, festivities, and sports. But it is also inhabited by a monad of his/her own, where his/her differential plus crashes and relates sui generis to the things he/she creates or generates that very same plus by turning into Energeia.

Let’s say that his emotional reserves become, on account of that plus, an effective fuel that sets determined potentialities into motion, and in that conversion certain biological ferment ––the “juices” of traditional medical symbolics–– is alleviated or is directly annulled, which for the rest of the mortals is efficient cause of his singular person.

Said in this way, the singular person is even more singularized in the production of unnatural things or is fit to the natural. On the contrary, by not being endowed with that plus, makes him/her fold to the species and, at best, looks for his/her difference through the signs serially produced by the liberal society of advanced capitalism for that very same operation for epidermic differentiation.

That is why cinema and its concept had to camouflage their operations simulating to fold to the forms of production proposed by the same liberal-industrial society and even imposed them as the only model and form of production. But also that camouflage or folding is fit for the industrial production mode that allowed the artist retake his role as an artisan or “grandmaster”, incorporating the type or figure described by Ernst Junger in his 1930’s Der Arbeiter (The Worker).

Better yet, the concept of cinema effectively articulated said type and figure in an efficient form in the so called “big studios” and then ––as in many other things–– it was the writer, the man of letters, the one who defined its description and its qualities.

- The expression ––“occupation of cultural power”–– is employed by Antonio Gramsci; we use it here with the necessary nuances of the case, to some measure different from the intention of its author and divulger.

- There’s the legend, or almost legend, that the intentions of his screenwriter, Carl Mayer, were entirely different; but if we wrote the story that way, we would be still in Paradise.

- It is obvious that this quaternary division wasn’t always respected, but it is canonical. From it we take Schubert’s Unfinished Symphony, which is not that “unfinished”.

- You can think of an Adagio, in the manner of the baroque sonata.

- The title chosen for this version of Bram Stoker’s novel comes, etymologically, from the term not-dead.

- A movement defined by litotes, a limitation of the character in an Allegro, we mean, not necessarily sad, but the absence of joy and happiness; similar to the definition of evil in theology: absence, deprivation or concealment of goodness.

- All this, just accepting what we postulated on Schopenhauer’s unknowable character of the pure musical; by this we mean that being music pure will, is unable to be represented to the ends of reasonable understanding and is, therefore, unable to be demonstrated.

- The monologue, or almost, said by the psychiatrist at the end of Hitchcock’s Psycho, is also a justification for the territoriality of cinema.

- Phrase coined by Stein in the novel Lord Jim, by Joseph Conrad.

- A procedure, point by point similar, to one later employed by Alfred Hitchcock in Psycho.