Are you actually that weak

that you don’t remember that time of grace?

Hugo Van Hoffmannsthal, Unending Time

Every work of art, or an attempt as such, is, before anything, an exchange. It tries to put a plus into circulation as exchange goods, a subjective private remainder, believed to be non-transferable for being situated in some remote emotional-spiritual bottom, but that seeks non-stop, maniacally, its place, its channel of circulation to be exchanged. And what would be the other good in the exchange? A reception. In the simplest act of this circulation, which is the oral narration, even in its minimal and even discredited expression ––that of the gossip––, it seeks to exchange the possession of something; a plus or particular remainder only in possession of a subjectivity that attempts to mediatize and objectify it into a story, and for that it seeks, simultaneously, an audition or a listening.

Such a story can lead to a tragedy. Not any other thing drives the point and even more than in the starting point in Othello, that begins with the telling of a gossip. Jealousy is a primordial part of the perverse axis of the story.

This has extended and horizontalized starting with the invention of the print, producing what McLuhan has effectively baptized as the “Gutenberg Galaxy”, which on our side we have extended to a Galaxy, back then not very attended, the “Griffith Galaxy”.

With it, this plus also expanded that necessity for exchange, since that from its very beginning counted with a growing and worldwide anonymous mass ––doubly anonymous–– of listeners that had to transform accordingly into seers.

With it, the transferred and badly comprehended relationship in the aesthetic fact between production and reception lent itself from the get-go to an unproductive and controversial tug-of-war about the intentions, or lack thereof, of an author and artist related to material concretion of that plus; be it as a story, plastic or tectonic form, dance, music, et al.

Of course, with cinema all these went to the extremes. Because cinema is the most extremist and radical manifestation in the History of Art. What was decreed shortly before as dissolved into the thin air, went back to solidify itself. As long as the production-reception dyad became part of the same circulation network of goods of advanced capitalist society. And it wasn’t by chance that the now momentarily in vogue “Austrian school of economics” ––it would be better to say “Austro-Hungarian school of economics”–– contemporarily coined the concept ––clearly in opposition to the Marxist economic theory–– of the “subjective value” of any merchandise.

In the middle of that coming and going ––given that the Marxism and its posterior ups and downs didn’t remain undaunted and started to operate as well into the ins and outs of the economy, known with the name of “politics”––, the “Griffith Galaxy” saw itself submitted to such symmetrical poundings. Especially, after it was put into world order by major Hollywood studios around 1930.

For historical-political reasons regarding the emotional-spiritual, this happened jointly, and had as its base a double diasporic alliance that, though occasional, produced, like many other times in the evolution of the arts and forms (politics included), a concrete effectiveness. In such a way, the prior post-romantic limbo was, if not eliminated, surpassed and set aside.

This did not last until beyond the mid-sixties of the last century, due that it wasn’t ––once again–– a “circulation of the elites”, according to Vilfredo Pareto. In this way, the major studios entered into an estate crisis.

During that downfalling decade of the “classical” system, that left behind one of the most solid forms of thought and poetry of the last century ––not to mention the only “organic construction” as such––, a sort of artificial respiration was looked for, that consisted in filling the studios with directors forged in the New York theatre and television. This was nothing more than asking their historical enemies for help.

Therefore, a group of malicious “innovators” destroyed the classical system of production; but not just “production” in the material-economic sense, but also in the emotional-spiritual sense, and in the common way of thinking as well.

People like Lumet, Frankenheimer, Pakula, Mulligan and a disgraced etcetera went into a delusion emulating the European cinema of those times; especially the ones produced in the double tract conformed by the nouvelle vague in Paris and the neorealism in Rome.

And all this happened while the cisatlantic European apprentices did nothing more than longing to shoot a classic genre film. A task that, generally, resulted in spectacular failure. As for the “neorealism”, it was diluted into costumbrist comedies with thick social allegories, until finishing their own expressive drift as well.

What happened then in Hollywood was ––to use a historical-stylistic simile, believed to be transparent–– like if baroque painting decided to associate with rococo decorators.

To continue with another simile ––History has similes or resources, never repetitions––, it can be said that the cathedrals were left standing; and though it wasn’t the case with the continuity of its material construction, it was for their expressive continuity. In any case, that is, until they are set on fire, like it happened recently with Notre Dame.

As a reaction to this stylistic chaos, or more precisely this upside down turn of the classicism, rose what we called self-conscious cinema. It made its appearance in the late sixties as a total controversial answer to the brief and unfortunate intermission of the anti-Hollywood television-theatrical generation, and by the way “progressive”; or what was understood as such over there in those years.

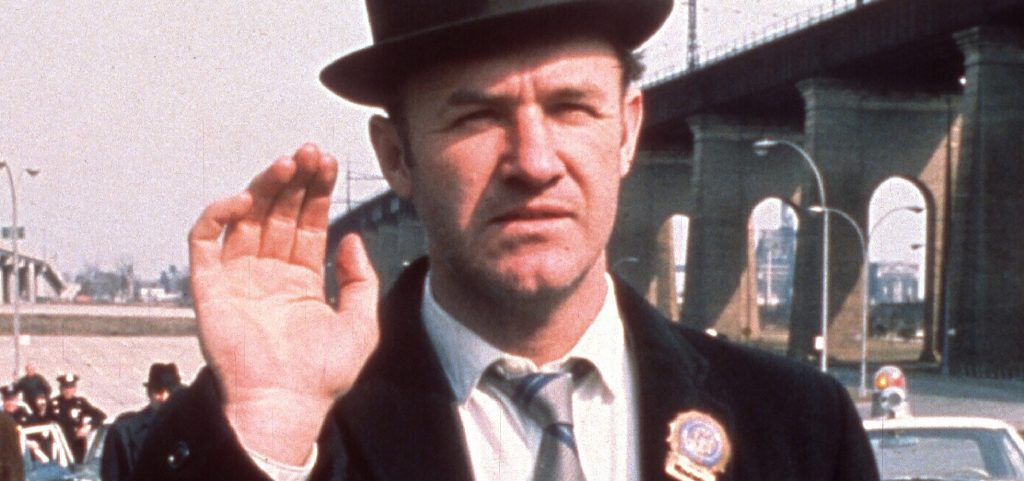

One of those films that pioneered self-consciousness ––celebrating these days the 50th anniversary of its release–– was William Friedkin’s The French Connection, that perimetered the terrain quickly and rotundly. Moved the goal zone and marked the playing field.

It is not about ––or at least not what we’re aiming for–– pointing out its technical novelty, its semi-documentary style, or even less the moral ambiguity between the pursuer and the pursued, because this was already found in Aeschylus. What is visible is always more comfortable and pleasing to the eyes.

If we want to point out an image-axis, a spiritual etymon and objective connection of all the film and the nascent self-awareness, What is that “French Connection”? By the way, an impossible connection for several metaphoric-dramatic reasons easy to find out in such a sense. The impossible connection, controversial and opposed, between the Hollywood tradition and the childish French exercises of that time.

A couple of years later a young Brian De Palma symbolically put it in operation with his film Sisters, on the basis of that metaphor of ––French speaking–– Siamese sisters surgically divided. Another impossible connection that had to be divided without any further thought.

In Friedkin’s film we see Popeye Doyle ––we mean, that “innocent eye” from Hollywood–– standing outdoors, freezing and eating a slice of frozen pizza, having to spy these two Frenchmen that gobble down a detailed banquet described meticulously: entrée, piece de resistance and desserts.

We have also all that series of stakeouts and high-speed car chases; flights of stairs whose top cannot be reached; treacherous snipers; especially that usurpation of the control of a moving train (Didn’t Hawks say that “a film is a long moving train”?) by a Frenchman that doesn’t know how to drive it; until that ending with the disappearance of that “French connection” that, like a ghost, evaporated among the destroyed (or deconstructed?) remains of an abandoned factory (studio?).

With all this analogic succession, doesn’t it mark with delicate yet brutal symbolic sanction that this priorly attempted French connection is nothing more than a ghostly illusion, whose emblems are two gobblers of sumptuary New York cuisine and a usurping machinist of a General that doesn’t know what to do with that machine launched at high speed?