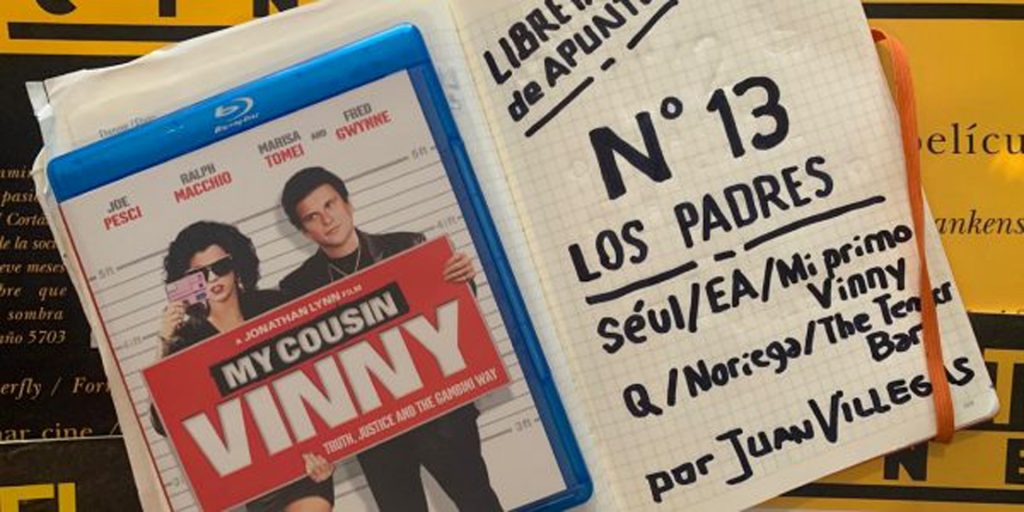

On Sunday, Seoul published an article by Gustavo Noriega remembering the 30th anniversary of the release of the first issue of El Amante. Noriega cites a text by Quintín, from January 1993, a review of My Cousin Vinny published in El Amante, a text that today from a distance is easy to read as a manifesto. Quintín said that “the dichotomy, European cinema as art, North American cinema as entertainment, is one of the aesthetic clichés that critics have been pursuing for years”. For many of us this is already obvious, but it was not at all in 1993. Although in a certain sense it is still an uncomfortable idea, because there are many who believe that good cinema should be presented with a package that announces that it is about an “important movie.” In another part of the article, Quintín noted that the standard of North American cinema was still very high, that this second or third line of films without prestige allowed in many cases social, cultural or political readings, especially when none of that was declaimed. And he forever described what he considered “the pleasure of common American cinema, which is not about a message to interpret, but about a cinematographic space to discover and enjoy.” Many of us who learned to watch movies while reading that first period of El Amante spent our time looking for that type of film, which despite not pretending to be masterpieces (or precisely because of that) offered us a noble and complex look at the world. and relationships between people, even if modestly hidden in the guise of simplicity, kindness and nobility. They are, in my case, unforgettable films, like October Sky (Joe Johnston, 1999), That Thing Called Love (Peter Bogdanovich, 1993) or Once Around (Lasse Hallström, 1991), although there are others that I no longer remember, that I enjoyed, which made me cry, think and laugh, but of which I retain not even the name of the director, but if I found them again by chance I would immediately recognize them. Years go by and we keep looking for them. And every now and then we find them. And we share the discovery among those of us who secretly love them, to feel accompanied, as if we were a secret sect.

To refer to that article by Noriega, which in turn cites that of Quintín´s, Diego Papic recalled in a tweet how his first meeting with El Amante was. There he was referring to an article by Gustavo Castagna about A Perfect World, in which it was said that the absence of the father was one of the essential themes of American cinema. And it made me think that in many of these noble but apparently minor films, those that American cinema luckily still knows how to make, the theme of the absence of the father was recurrent. That had to mean something. And I think I figured it out. Cinephilia cannot be anything other than the way we have to save ourselves from something, to patch holes, to find meaning in a world that we look at with perplexity. Kind and noble films do not offer us an antidote to that hostility, they are not even a way to escape from pain. It is, on the contrary, a universe in which we reflect ourselves, which exposes us to our worst ghosts, but which at the same time protects us, gives us a home, teaches us to understand what life is about. Like a father is supposed to do with a son.

The noble films are the father that many of us did not have. That feeling of protection and revelation that these films offer us, due to their very cinematographic nature, is doubled in turn when the theme it raises is the search for the father and the discovery that this pain and absence can only be replaced with one’s own life, with the construction of a calling, with the adventures of love and with the affection and trust of other people, who are not our parents, but who help us to continue, to grow and to believe in ourselves.

I end this column without mentioning The Tender Bar yet, which can be seen on Amazon Prime Video. Well, this beautiful, kind and noble film is about all that I have just written.